As 2024 marks 300 years since the establishment of Asaf Jahi dynasty, a look back at the drama that unfolded during the succession of first Nizam Mir Qamruddin, also marking the debut of European powers in Deccan’s polity

Published Date – 30 March 2024, 10:29 PM

–Rahul Milind

“Mankind should not be likened to so many ears of barley, wheat and maize which grow anew every year,” warned the ‘Servant of the Mughal Emperor’ in his last will which he dictated just days before his demise in 1748. Twelve years prior, he was honoured with the title of ‘Asaf Jah’ by the Mughal Emperor Muhammad Shah for defeating the then Mughal Governor to the Deccan, Mubarez Khan, and establishing his own dynasty under him. ‘Asaf Jah’ was the highest title awarded by the Mughals ever, drawing a parallel to Asaf, the Grand Wazir in the court of the Biblical ruler King Solomon.

Mir Qamruddin, the grandson of Chin Qalich Khan who helped Aurangzeb unfurl the Mughal flag over the Deccan, was sovereign by himself in 1724 and the founder of the Asaf Jahi dynasty, popularly known as the Nizams of Hyderabad. He would go on to rewrite the future of the Qutb Shahi soil. Be it the grandeur of the magnificent Taj Falaknuma that leaves one in awe today or the countless lives the roof of Osmania Dawakhana saved and gave rebirth to, the contributions of the Nizams were unparalleled and their days larger than life, serving the city of Hyderabad till date, even nearly 77 years after their downfall.

Mir Qamruddin Nizam-ul-Mulk Asaf Jah, the first Nizam of Hyderabad, carried with him the intellect, power and strength of Mughal blood in every possible way. Had his successors followed his last testament diligently, history would have been kinder to them in the centuries that followed.

Political Twist

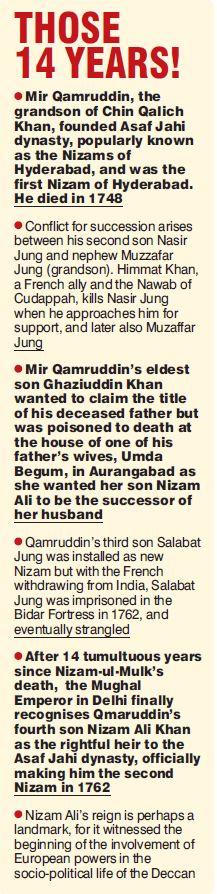

After Qamruddin’s death in 1748, the succession was not immediate, thanks to the dramatic political turn of events, and the thirst for power among many. With the Islamic law laying no defined set of rules regarding the emperor’s succession, it was not certain or clear as to who would take up the mantle. Though Qamruddin had breathed his last, summoning his second son Nasir Jung, there arose a conflict for succession between Nasir Jung and his nephew Muzzafar Jung (Qamruddin’s grandson). As both parties split ways, they were backed by the new, foreign powers, alien to this part of the subcontinent and toiling to establish their identity.

While the British backed Nasir Jung at Fort St George, Muzzafar was supported by the French — Joseph Dupleix, the French Governor of Pondicherry. As the conflict expanded, bringing the European forces into the picture, Nasir Jung marched with his troops to what was considered the most impregnable fort in South India, the fort at Gingee in Tamil Nadu, which had withstood Aurangzeb’s 12-year-long siege. Looking at the strength of Nasir’s army, the French troops refused to fight and retreated to Pondicherry, leaving the young Muzzafar at the mercy of his uncle, who, however, did him no harm but just captured him.

Fate’s Other Plan

At a time when Nasir Jung thought he would rise to become the second Nizam, fate presented him with a different plan — Dupleix arranged a small French force, along with soldier Charles de Bussy, who stormed Gingee after Nasir’s forces returned to Hyderabad having assumed that the conflict was over. Himmat Khan, a French ally and the Nawab of Cudappah, shot and killed Nasir Jung when he approached him for support. With Nasir Jung out of the way, the French, amid festive pompoms and firing of the salutes, installed Muzaffar Jung as the new Nizam at Pondicherry — a deliberate step taken to convey to the Islamic world that the power had now been passed from the Viceroy of the Deccan to the French. Muzaffar wrote history as the first Indian ruler to engage the military under a European command in exchange for grants for territory.

The inauguration of Muzaffar, however, was never officially recognised by the Mughal Court in Delhi, and his ‘reign’ would only last for six weeks. For plotting the death of Nasir Jung and helping the French and Muzzafar rise to power, the Nawab of Cudappah demanded exorbitant sums and rewards in return. Fearing any impending conflict, Muzzafar, along with French forces led by de Bussy, marched his way back to Hyderabad. He was attacked by Himmat Khan and his forces near the Eastern Ghats. Activating the valour of the Mughal blood that ran in his veins, passed on from his grandfather and uncles, the young Muzzafar stormed on his elephant against the Nawab’s army, only to be hit by a bow in his eye that killed him instantly. However, as long as their influence continued in the Deccan, Muzaffar’s death didn’t really affect the French, who quickly installed Qamruddin’s third son Salabat Jung as the new Nizam.

To eliminate any further issues of succession, Salabat imprisoned two of his younger brothers, Nizam Ali and Balasat Jah, while his eldest brother, Ghaziuddin Khan, who was then serving as a Minister at the Mughal Court started marching southwards to claim the title of his deceased father. However, Ghaziuddin’s luck could only bring him till Aurangabad, to the house of one of his father’s wives, Umda Begum, who wanted her son, Nizam Ali, to be the successor of her husband. Accepting her invite, he stayed at her place overnight, where he was poisoned to death, and completely erased from the picture. Even though Salabat took over the dynasty, his 11-year rule was never recognised by the Emperor at Delhi, nor was it appreciated by the French.

The Rightful Heir

The English East India Company didn’t hold much power in Hyderabad initially, for Britain was not involved in any way with the French yet. However, the outbreak of the seven-year Anglo-French war in 1756 completely altered the foreign-power dynamics, especially in the Deccan. Joseph Dupleix was called back to Paris as was Charles de Bussy two years later when asked to withdraw the French troops from Hyderabad. With the French now gone, Salabat was left on his own, weak and without any support. He was imprisoned in the Bidar Fortress in 1762 where he was eventually strangled.

It was after 14 tumultuous years since Nizam-ul-Mulk’s death that the Mughal Emperor in Delhi finally issue a farman recognising Qmaruddin’s fourth son Nizam Ali Khan as the rightful heir to the Asaf Jahi dynasty, officially making him the second Nizam in 1762. The then 28-year-old would go on to become the second-longest serving Asaf Jah, succeeding Hyderabad’s very own ‘Beloved’, Asaf Jah VI Mir Mahbub Ali Khan, who would be born a little more than a century after Nizam Ali’s accession and the last Nizam to lead his armies into battlefields.

Nizam Ali’s reign is perhaps a landmark, for it witnessed the beginning of the involvement of European powers in the socio-political life of the Deccan — especially the British, who would cast a spell of gloom over the Asaf Jahi lineage in the following decades. His 41-year reign was marked by no less than six treaties with the British due to Nizam’s indecisive hopping between his ambitions and the practical reality that lay far from the former. By the turn of that century, though Hyderabad had risen to become the largest and most important princely State in the Indian subcontinent, it had completely fallen into British hands.

Raja Raghunathadas

As this March marks the 290th birth anniversary of Asaf Jah II Nizam Ali Khan and 300 years since the establishment of the Asaf Jahi dynasty this year; one must not forget the intellect and equally significant valour displayed by Raja Raghunathadas, a Hindu, during the battle between Himmat Khan and Muzaffar Jung.

In an interesting and perhaps lesser-known anecdote, after Muzzafar Jung was shot in his eye by the Nawab of Cudappah, it was Raghunathadas who sat behind Muzzafar’s body, removed the arrow, and moved his lifeless arms, as if their leader was still alive. By asking for food and water occasionally, moving his head and directing his soldiers often to storm at their opponents, he sent out a message of strength among Muzzafar’s troops, who eventually chased away and beheaded the Nawabs who challenged them. It was only after the battle had ended and the music of victory triumphed did everyone meet the truth that their ruler Muzzafar Jung was long dead. One can’t help but wonder that if not for Raghunathadas, would the Asaf Jahi lineage still have flourished, and go on to reshape Hyderabad and the Deccan at large, establishing themselves as the ‘Greatest Mohammedan Power in Post-1857 India’.

References

Zubrzycki, John. ‘The Last Nizam: The Rise and Fall of India’s Greatest Princely State’

Prasad, Rajendra. ‘Asaf Jahs of Hyderabad’ Vikas Publishing House Pvt Ltd. New Delhi, 1948

(The author is an aspiring storyteller and a documentary filmmaker. He has a degree in History from Krea University)

Rahul Milind