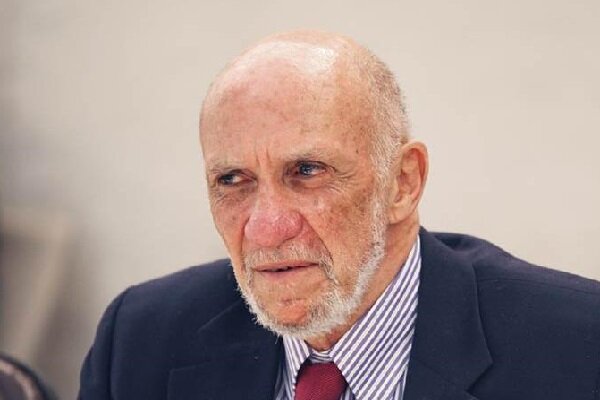

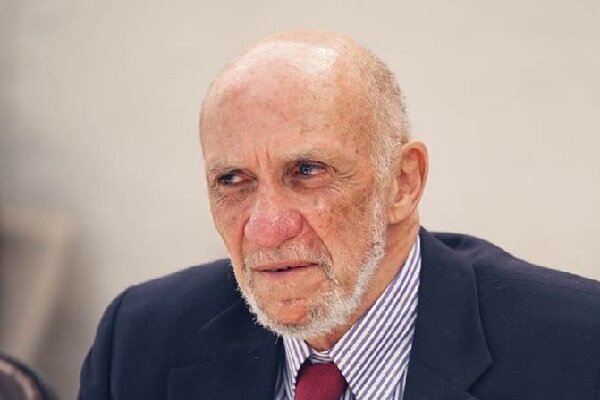

Richard Anderson Falk, the former special rapporteur on human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967 and an American professor emeritus of international law at Princeton University made the remarks in an interview with Mehr News Agency about the role of the role of the late Imam Khomeini in the Islamic Revolution in Iran.

A few days before the victory of the Islamic Revolution of Iran, you had a meeting with Ayatollah Khomeini. What were the issues raised in the meeting?

The conversation was a few days before Ayatollah Khomeini returned to Iran after being resident in France during most of the revolutionary challenge directed at the Shah’s governing structure after being expelled by Iraq. It was for me a memorable meeting after ten days in Iran to understand the revolutionary developments better. We were deeply impressed by Ayatollah Khomeini’s keenness of mind and clarity of vision about why a transformed Iran was necessary and desirable. I was particularly struck by the uncompromising nature of AK’s vision, which clearly rejected the reform of the old order and the establishment of a new order from top to bottom, starting with the institutions of the state.

I would stress a few themes from a very long conversation:

– Uppermost in AK’s mind in our meeting was the menacing prospect of a counterrevolutionary intervention organized by the United States so as to restore the Shah to the Peacock Throne. He seemed to be worried that what happened in 1953 to reverse the outcome of democratic elections that had brought the nationalist leadership of Mossadegh to power would be repeated. He sought our opinion as Americans, but we could only express our hope that such an intervention would not happen, and we did indicate that the Carter presidency had important pro-interventionist high officials, including the National Security Advisor, Zbigniew Brzezinski;

– AK also expressed the view that he hoped that normalized relations with the US would become possible but expressed his opinion that this could only happen if the U.S. refrained from interference in Iran and fulfilled existing contracts, including those concerned with the national security of Iran, and most of all, respected the will of the Iranian people as embodied in the revolutionary success;

– AK strongly emphasized an insistence on comprehending the anti-Shah revolution was in its essence as Islamic.

– AK also suggested to us that there should be accountability for the crimes of the Shah.

– AK also indicated that he hoped personally to resume a religious life upon returning to Iran.

– AK also expressed open opposition to other instances of dynastic rule in the Islamic world. He made clear that some monarchies were inconsistent with the principles of Islam.

That meeting was before the victory of the Islamic Revolution. What was the special feature of Ayatollah Khomeini that attracted your attention? Was Ayatollah Khomeini sure of the victory of the revolution?

It was our impression that AK was very confident that with the abdication of the Shah, which had occurred a few days earlier, the victory of the revolution was assured, and only intervention or a staged coup could alter this outcome. His focus was upon defending the revolutionary victory against the future. Attempts to reverse the will of the Iranian people and how to plan a smooth transition from the old imperial order of the Shah to some version of an Islamic republic.

We were particularly struck by the moral and political clarity of AK, and to some extent by the severity of his demeanor, which seemed averse to any kind of compromise with respect to the transition from the old Iran to what he envisioned as the new Iran. It became evident to us that AK regarded the revolution as motivated by the desire to obtain deliverance of the Iranian people from corrupt, secular, modernizing, oppressive governance structures to be replaced by structure rooted in Islamic values, assuring virtuous policies and practices.

In defense of the Islamic Revolution of Iran, you wrote an article in the New York Times that led to attacks on you. Why did you write that article and what were the attacks?

I was encouraged to write the article by the Opinion Page Editor of the NY Times who acknowledged to me that very little was known about AK by the American people and that their own coverage had been inadequate. I had the impression that this interest arose because there was the view that struggle was over, and that the forces led by AK had prevailed, and it was important to grasp this new reality so as to adapt to this unexpected nonviolent expression of the self-determination rights of the Iranian people.

I was attacked because the article was critical of the Shah’s regime and expressed guarded optimism about the future of Iran under this new revolutionary leadership. The Shah’s government was regarded as a strong regional ally, a source of oil for the West, a crucial element in the U.S. effort to contain Soviet expansion, and an ally willing to take heat for exporting oil to Israel and apartheid South Africa.

In the conversation, you introduced Ayatollah Khomeini as a real and elite revolutionary. What was the difference between the Iranian revolution and the other revolutions of the 20th century, and how much do you appreciate the role of Ayatollah Khomeini in leading the Islamic Revolution in Iran?

AK struck me as a true revolutionary, but not in the familiar modes of left secular politics, inspired by Marxist and Leninist thought. AK was definitely not a reformer, but someone who wanted an entirely new governing structure animated by Islamic values that were not oriented around Enlightenment rationalism, leftist proletarianism, and the values and priorities of modernity as it evolved in the West after the Industrial Revolution. Unlike other Western revolutions, AK had advocated and practiced a politics of revolutionary nonviolence in the manner of Gandhi throughout the revolutionary struggle, but it was pragmatically motivated.

In your opinion, what were the characteristics of Ayatollah Khomeini’s personality that attracted the people and revolutionary groups and ultimately led to the victory of the Islamic Revolution?

As I suggested earlier, AK conveyed visionary confidence that what he proposed was the embodiment of Islamic virtue and teaching, and that this was the basis for carrying the revolution forward after the fall of the Pahlavi dynasty. Throughout the revolution when many believed that AK should accept a compromise, and if that was not done, his movement would be defeated and destroyed by a military coup or outside intervention, or some combination. As someone rooted in religious tradition and conviction, who had borne witness to his beliefs by accepting exile rather than defer to the authority of the Shah, AK never wavered in the course of prolonged exile in Iraq. AK remained firm in his belief that the Iranian people deserved a government that was not beholden to Western decadence and its hostility to Islam. In this sense, AK embodied an opposition leader who through ideas and personal courage inspired the people of Iran to risk their lives in fighting for a new political order, and adopted tactics that led to a surprise victory over what was regarded as the strongest and most ruthless regime in the Middle East.

What is the legacy of Ayatollah Khomeini for the revolutionary and freedom-seekers of other countries?

The legacy of AK may be best grasped by comparing the fate of Egypt since the Arab Spring of 2011 and that of the Islamic Republic of Iran. The overthrow of Mubarak by the Egyptian masses was followed by an accommodation with the governing structures of the old order, which directly led to tensions that generated a counterrevolution that restored the old regime to power in a harsher form than it had possessed before the Arab Spring uprising. In contrast, the clarity of AK’s practice and policies led to the durability of the Iranian revolutionary process in the face of many threats to weaken or destroy what Iran had become. This durability survived a Western-backed all-out military attack on Iran in 1980 designed to weaken if not reverse the revolutionary changes brought about in 1979, and through continuous harassment and threats from such regional adversaries as Israel and Saudi Arabia with nuclear weapons as well as geopolitical pressures mounted by the United States, backed by many threats and policies of ‘maximum pressure.’

The legacy of AK can also be understood by his unconditional insistence on a clean break with Iran’s dynastic secularism and its replacement by a revolutionary new political order built on the firm foundation of Islamic principles, which not only constructed an Islamic state, but reshaped the education, social mores, and the economy of the country to harmonize with this pervasive Islamic profile. To realize this vision that would have seemed utopian until it became established in the first years of AK’s leadership. Meeting the many challenges directed at Iran’s political survival by internal, regional, and global adversaries should also be considered as one of the great de-westernizing achievements of the last 75 years. It was a largely unacknowledged contribution to the demise of European colonialism. This remains an ongoing struggle that has changed its character over time, although not its essence, and is not fully resolved. A major dimension of AK’s legacy is that he managed to bring stability to the Islamic Republic by overcoming formidable obstacles during the first difficult decade of its existence. Unfortunately, for Iran, the struggle goes on with no end in sight and even intensified confrontation given the belligerent coordination of anti-Iranian by the governments of the United States, Israel, and Saudi Arabia.

Republished