With ships traversing the Red Sea coming under attack, the world’s maritime business sails into choppy waters

Published Date – 27 January 2024, 11:59 PM

Ships on seas have been the targets of pirates since ancient times. The exploits of both fictional as well as fictionalised pirates — John Silver, Vikings, Jack Sparrow, etc — have captured our imagination. From attacking Roman ships carrying grain and olive oil to ransom kidnapping, disrupting sea trade has had a long history. Add the geopolitical problems and climatic challenges of today, and the sea is caught deeper in rough weather.

The recent attacks on commercial vessels in the Red Sea by Yemen’s Houthi rebels have scared off not just some of the world’s top shipping companies but also governments across the world. The US-led international naval coalition of around 20 countries, Operation Prosperity Guardian, protects ships transiting the Red Sea. “This is an international challenge that demands collective action,” stressed Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin recently.

The Houthis, backed by Iran, have targeted Israeli-linked vessels during Israel’s war with Hamas but have escalated their attacks in recent days, hitting or just missing other ships with drones and missiles. Most attacks are launched from near the Bab el-Mandeb Strait that ships pass through to enter the Red Sea from the Indian Ocean. At its narrowest point, the strait, separating Yemen and Djibouti, is only 29 km wide. The Red Sea is also the only route to the Suez Canal.

The Red Sea has the Suez Canal at its northern end and the Bab el-Mandeb Strait at the southern end leading into the Gulf of Aden. It’s a busy waterway with ships traversing the Suez Canal to bring goods between Asia and Europe. Around 20% of global container volumes, 10% of seaborne trade and 8-10% of seaborne gas and oil pass through the Red Sea and Suez route.

“This is a problem for Europe. It’s a problem for Asia,” said John Stawpert, senior manager of environment and trade for the International Chamber of Shipping, which represents 80% of the world’s commercial fleet. Around 40% of Asia-Europe trade normally goes through the waterway. “It has the potential to be a huge economic impact.”

The disruptions from the Red Sea couldn’t have come at a more precarious time. The Panama Canal, a major trade route between Asia and the United States, is facing a severe drought, forcing authorities to slash ship crossings by 36%. Some companies had planned to reroute to the Red Sea to avoid delays at the Panama Canal. Now, that’s no longer an option for most. Panama Canal Administrator Ricaurte Vásquez estimates that dipping water levels could cost them between $500 million and $700 million in 2024.

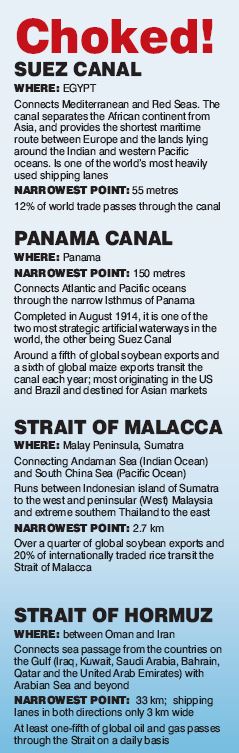

Choke Points

“Global supply chains have become a lot more important for everyday life, so the impact of disruptions in the Red Sea is now much bigger. Crucially, Bab el-Mandeb is only one of several maritime choke points that are vital for world trade” write Sarah Schiffling of Hanken School of Economics, and Matthew Tickle, University of Liverpool, in The Conversation.

Choke points are narrow parts of main trade lanes, usually straits or canals. As the geopolitical weaponisation of supply chains increasingly becomes a part of economic statecraft, their vulnerability grows. As the Houthis have shown, disrupting global trade at one of these choke points does not require huge military power, they say.

Sea is the main transport mode for global trade as around 90% of goods are carried over the waves. The Strait of Malacca, among the 14 major chokepoints, is the most important. It links the South China Sea with the Indian Ocean, carrying 40% of the world’s trade. Piracy is a major issue here.

Alternative routes to them are difficult. The Northern Sea Route is 40% shorter than the alternative via the Suez Canal for connecting Asia to Europe. But ice makes it navigable for no more than five months per year and there are concerns about the impact of ships on the fragile Arctic ecosystem.

The Strait of Hormuz has a long history of tensions. At least one-fifth of global oil and gas transports is shipped through the 39-km wide stretch of sea between Oman and Iran. By blocking this choke point, Iran could throw the global economy into serious disarray.

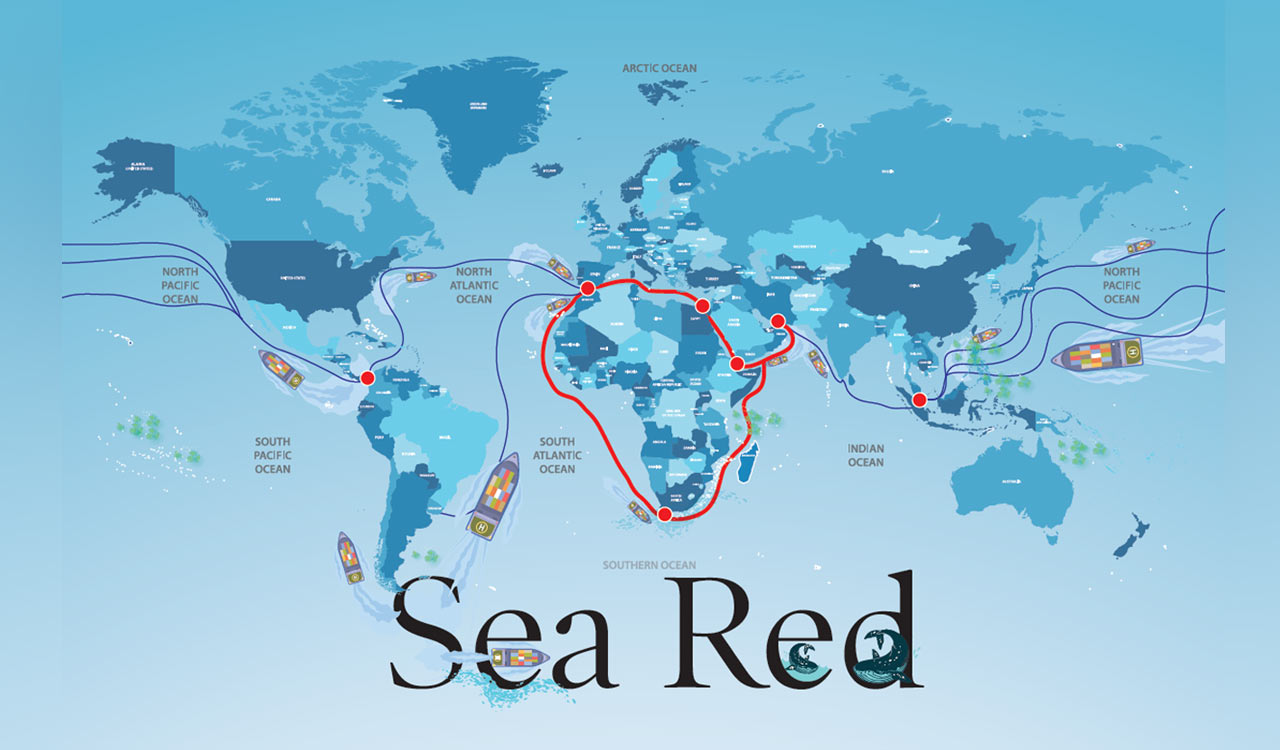

Then there is the railway line linking China to Europe which has seen significant growth in freight transport in recent years. But both rail and Northern Sea Route connection are affected by sanctions on Russia. What is left for most who are keen to avoid the Red Sea is the long detour around Africa.

In the case of re-routing, ships will have to go around the Cape of Good Hope at the bottom of Africa, adding 10 days or even longer to voyages. This means, companies will have to add more ships to make up the extra time, and burn more fuel — both of which would release more climate-changing carbon dioxide

Unstable Horn of Africa

Sudan’s armed forces and the rival Rapid Support Forces have been fighting for control of Sudan since April. Long-standing tensions have erupted into street battles in the capital Khartoum and other areas including the western Darfur region.

Tension has also been rising after land-locked Ethiopia signed an agreement on January 1 with Somaliland to give it access to the sea. Somaliland in return expects Ethiopia to recognise the region as an independent state, which angers Somalia. Since declaring independence from Somalia in 1991, Somaliland has operated as a fully functional de facto state, boasting its own defined territory, population and government. The two crises are threatening regional stability in the Horn of Africa.

Impact on Trade

There are about 400 commercial vessels transiting the southern Red Sea at any given time. Opened in 1869, the Suez Canal is one of the busiest canals in the world. In 2022, 23,583 ships used this route.

Some Israeli-linked vessels have started taking the longer route around Africa and the Cape of Good Hope, said Noam Raydan, senior fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. That lengthens the trip from around 19 days to 31 days depending on vessel speed, increasing costs and adding delays.

The sailing time between eastern Asia and western Europe can increase by 25-35% when ships use the Cape route. For instance, a vessel travelling at 13.8 knots per hour (the current average speed of global container ships) between Shanghai and the Port of Felixstowe in the UK will see its sailing time increase from an average of 31 days to 41 days when sailing around the Cape.

Jan Hoffmann, a trade expert at the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), said early data from 2024 show that over 300 container vessels, more than 20% of global container capacity, were diverting or planning alternatives to using the Suez Canal. Many are opting to go around the Cape of Good Hope in Africa.

The cost to ship, a standard 40-foot container from China to northern Europe, has jumped from $1,500 to $4,000, according to the Kiel Institute for the World Economy in Germany. But that is still far from the $14,000 seen during the pandemic. The delays contributed to a 1.3% decline in world trade in December, reflecting goods stuck on ships rather than being offloaded in port. According to the International Monetary Fund blog, when freight rates double, inflation increase by about 0.7% percentage points.

Raising Tensions

The strikes in the Red Sea threaten to ignite tensions in the Middle East. It’s also affecting shipping for the Middle East nation of Qatar, one of the world’s top natural gas suppliers.

Saudi Arabia, which supports the Yemeni government-in-exile that the Houthis are fighting, sought to distance itself from the attacks as it tries to maintain a delicate détente with Iran and a cease-fire it has in Yemen. The Saudi-led, US-backed war in Yemen that began in 2015 has killed over 150,000 people, including fighters and civilians, and created one of the world’s worst humanitarian disasters.

International Mission

Under the new mission to guard the sea, the military ships will not necessarily escort a specific vessel but will be positioned to provide umbrella protection to as many as possible at a given time. The United Kingdom, Bahrain, Canada, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Seychelles and Spain have joined this new maritime security mission. Some of those countries will conduct joint patrols while others provide intelligence support in the southern Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden.

The Red Sea crisis is causing significant disruptions in the shipment of grains and other key commodities from Europe, Russia and Ukraine, leading to increased costs for consumers and posing serious risks to global food security

One notably absent participant is China, which has warships in the region, but those ships have not responded to calls for assistance by commercial vessels, even though some of the ships attacked have had ties to Hong Kong. Several other countries have also agreed to be involved in the operation but prefer not to be publicly named.

The attacks on the Red Sea by the Houthi rebels and on other choke points by pirates, or ship stoppages by warring nations, prove, at least for now, that “whosoever commands the sea commands the trade.”