Capitalists accumulate wealth and income from the surplus value created by labourers leading to imbalance in income and wealth distribution

Published Date – 11:45 PM, Tue – 14 November 23

Capitalists accumulate wealth and income from the surplus value created by labourers leading to imbalance in income and wealth distribution

By Dr Prashant Kumar Choudhary, Jadhav Chakradhar

Infosys co-founder NR Narayana Murthy ignited a spirited debate with his proposal that working 70 hours a week would accelerate the nation’s progress. While some applaud the call for dedication and productivity, others expressed concerns regarding work-life balance, well-being and the sustainability of prolonged working hours. Within this context, we explore the nexus between working hours, GDP per capita, and the wealth gap in selected countries. Finally, we discuss working hours in India’s flat-from/gig economy.

Historical Correlation

The OECD report from 2021, titled ‘How Was Life? Volume II: New Perspectives on Well-being and Global Inequality since 1820,’ provides an insightful analysis of the historical evolution of working hours in the manufacturing sector globally by taking 4,300 observations across 120 countries. The data reveals that in the 19th century, workers in manufacturing toiled for demanding hours, ranging from 60 to 90 hours per week. The period following World War I marked a significant turning point, as the introduction of the eight-hour workday triggered a rapid decline in weekly working hours.

Subsequently, in the 20th century, adopting the five-day workweek further reduced the working hours to 48. While one might assume a straightforward relationship between GDP per capita and working time, where rising incomes lead to decreased working hours, historical data presents a more nuanced picture. An interesting observation from this report is that working hours decline notably as GDP per capita remains below $20,000.

However, once a country’s GDP per capita surpasses this threshold, the average workweek converges to around 40 hours per week, irrespective of the nation’s income level. This shows that working time is subject to various complex factors, leading to periods of stability and change in response to economic growth and societal shifts. However, on average, there is a simple inverse relationship between the GDP per capita and working hours.

Other Economies

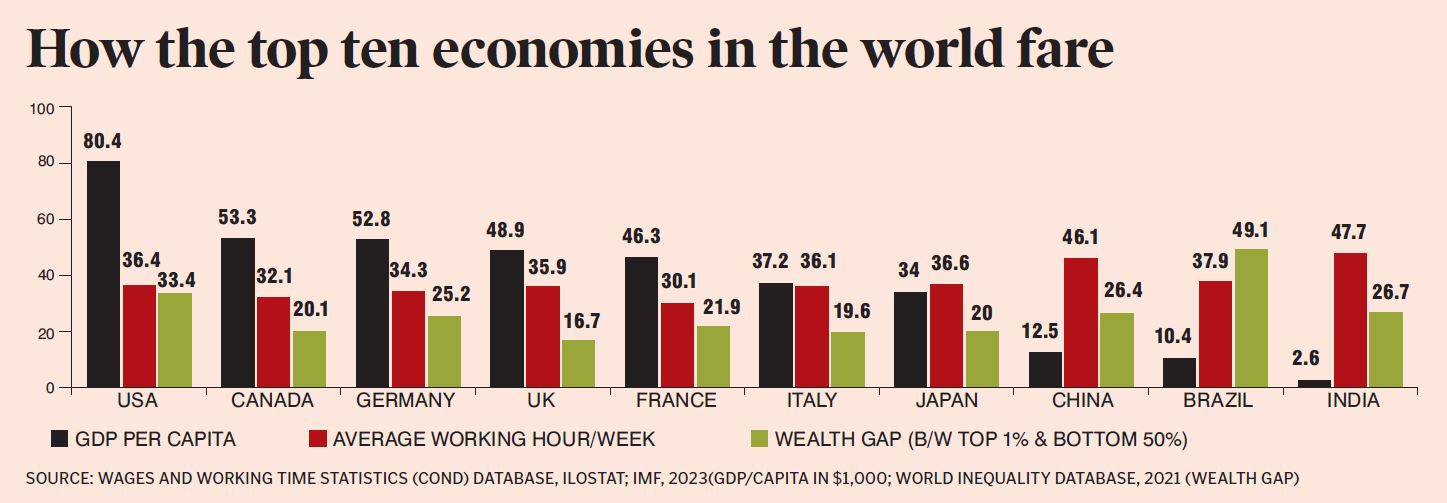

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO), individuals are recommended to work a maximum of 48 hours per week on average for 52 weeks. In India, employed individuals already work an average of 47.7 hours per week. When we compare this to the top ten economies in the world, it becomes apparent that Indians are already working longer than their counterparts in these leading economies. However, India has the lowest GDP per capita among the top economies.

An intriguing observation arises when examining countries such as India, China and Brazil. Despite having the highest average working hours per week, they have the lowest GDP per capita among these nations. This underscores the unique dynamics of these countries, where a high level of labour input does not necessarily translate into higher income on a per capita basis, which may prompt further investigation into the factors influencing this disparity.

An increase in the income or wealth of the rich one per cent is one thing, and that of the bottom 50 per cent population is another. India’s economic story is primarily driven by the growth of the former, with the existence of high unemployment in the latter. In October, India’s unemployment rate crossed just above 10 per cent (10.05%) amid a GDP growth rate of 7%. This shows a much-contested phenomenon of ‘jobless growth.’ It is also true that India registered a consistent rise in the GDP/per capita post liberalisation ($304 in 1991 to $2600 in 2021), and the poverty rate declined from 51 per cent to 16.4 per cent during the same period. However, in absolute terms, India had 230 million poor during 2019-21 and has a long way to go to before it pulls out every individual out of poverty.

Returning to the idea of higher working hours, it has been debated whether higher working hours would lead to higher economic growth. It is imperative to assert that productivity is not inherently correlated with increased working hours. To illustrate, let us consider the report of Fairwork India, 2023, on platform economy, which evaluated 12 platforms such as Amazon Flex, Flipkart and Swiggy. The workforce engaged in the platform economy often faces a distinct compensation structure, wherein payment is not strictly tied to the hours worked and job security is seldom guaranteed.

While fostering flexibility, this arrangement can potentially exacerbate income inequalities and give rise to work-life balance issues. As Fairwork has consistently emphasised, working conditions within the gig economy consistently fail to meet acceptable standards, leaving workers vulnerable to precarious circumstances.

Ultimately, the ramifications of such a directive extend to a nation’s economic development and the well-being of its workforce. Advocating extended working hours as a means of bolstering economic growth inadvertently reinforced the interests of the capitalist class.

Furthermore, the absence of guaranteed minimum wages in scenarios where individuals might work beyond 48 hours, such as in a platform economy, contributes to the concentration of wealth among the industrial class. This can relegate the working class to a subsistence level, perpetuating economic disparities. It is crucial to recognise that the pursuit of higher working hours should be evaluated in the context of broader economic and societal implications, including its influence on income distribution and mental health concerns.

Marx’s View

The idea of working 70 hours per week raises concerns about excessive working hours, which aligns with Marx’s critique of capitalism. Marx argued that capitalists aim to extend the working day to maximise profits, often leading to prolonged and exhausting work hours for the labouring class. Working such long hours can result in the overexploitation of workers, as they provide their labour power for extended periods without a proportionate wage increase.

Additionally, when workers are compelled to work extraordinarily long hours, the potential to extract surplus value by capital increases significantly. The surplus value generated during extended workdays becomes a source of profit for employers, a concept central to Marx’s analysis of capitalism. In this context, the discussion of working 70 hours a week can prompt questions about the distribution of surplus value and fair compensation.

Capitalists who accumulate wealth and income from the surplus value created by labourers benefit from labourers’ long workdays. This imbalance in income and wealth distribution is a critical concern in many countries, including India, where income inequality is increasing.

The concept of working 70 hours per week proposed by Narayana Murthy is fallacious and questionable. Rather than relying on an exceptionally long workweek, a more viable approach would be to invest in enhancing education and workers’ skills. By equipping the workforce with improved knowledge and skills, individuals can contribute more effectively to the economy, leading to sustainable development and improved living standards.