We will not be gauged solely by material wealth or tech advancements, but by the purity of the air we pass on

Published Date – 28 March 2024, 12:01 AM

PK Joshi

Air pollution emerges as a critical environmental challenge, bearing significant health implications. Among its array of components, Particulate Matter 2.5 (PM2.5) looms large as a principal concern. PM2.5 denotes tiny particles suspended in the air, measuring 2.5 micrometres or less in diameter. These particles emanate from diverse sources such as vehicular exhaust, industrial operations, construction undertakings, biomass burning, as well as natural phenomena like wildfires and dust storms.

PM2.5 poses a heightened risk due to its tiny size, capable of infiltrating deep into the respiratory system and even entering the bloodstream, precipitating health problems including asthma, bronchitis, lung cancer, heart disease and premature mortality. Moreover, prolonged exposure to heightened levels of fine particulates can impede cognitive development in children, exacerbate mental health issues and exacerbate existing ailments like diabetes. Its ramifications extend to complex environmental processes impacted by the Earth’s climate, which is also related to fatalities.

Poor Record

It is imperative to monitor air quality levels and take proactive measures to mitigate PM2.5 emissions, crucial for safeguarding public health and environmental preservation. The 6th Annual World Air Quality Report 2023 by IQAir, a Swiss air quality technology firm, endeavours to apprise individuals, organisations and governments of air quality conditions for necessary intervention.

Drawing from data collected from 7,812 locations, encompassing 30,000 regulatory air quality monitoring stations and low-cost sensors across 134 countries, the report highlights that only 10 out of these nations have managed to meet the WHO annual PM2.5 guidelines (=5 μg/m3). With a mere 9% of cities globally meeting this benchmark, there remains significant work ahead to combat air pollution effectively.

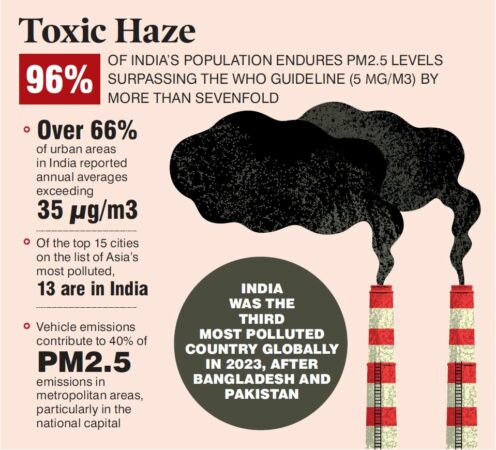

India, ranked third with regard to air pollution in the region following Bangladesh and Pakistan, grapples persistently with severe air quality issues. The annual average concentration of PM2.5 increased marginally in 2023 to 54.4 μg/m3 compared with 53.3 μg/m3 in 2022. In the National Capital Territory of Delhi, the concentration surged by 10% in 2023, peaking at 255 μg/m3 in November.

Alarmingly, 96% of India’s population endures PM2.5 levels surpassing the WHO guideline by more than sevenfold. This concerning trend reverberates across cities, with over 66% of urban areas in India reporting annual averages exceeding 35 μg/m3. India boasts an extensive air quality monitoring network, hosting more stations than all other regional countries combined, with data collected from 256 cities in 2023. Despite this, a significant proportion of Indian cities feature prominently in the list of Asia’s most polluted, with 13 out of the top 15 located in India.

Persistent Challenges

In northern India, including Delhi, persistent challenges stem from a combination of factors such as vehicle emissions, construction, coal combustion, waste burning, biomass burning for heating and cooking and often crop burning. The annual burning of crops in northern India and neighbouring regions in the winter frequently leads to air quality reaching emergency levels. Vehicle emissions notably contribute to 40% of PM2.5 emissions in metropolitan areas, particularly in the national capital.

Recently, the scientific community has explored cloud seeding as a potential solution to alleviate Delhi’s smog. Measures have been implemented, including the prohibition of coal usage for most commercial and industrial activities, enforced with hefty fines for violators. Despite efforts to reduce coal dependency, the region and the country still face numerous challenges in combating air pollution.

The air quality report may have multiple limitations, including the aggregation of the data sourced with a variety of uncertainties and varied spatial distribution density. For instance, Begusarai, in eastern Bihar, has emerged as the most polluted metropolitan area in this report for the first time. However, there is no scientific evidence of pollution in this city, except for the possibility of solid fuel or solid waste burning being a contributing factor.

Of particular concern is the calculation of the annual average PM2.5 concentration, which incorporates population data to provide a human-centric perspective on air quality in a given area. The use of population weighting as a normalisation factor can yield biased results, exerting a notable influence on Asian countries like India and specific hotspots such as Delhi. Another unofficial reason to doubt these reports might stem from concerns about potential conflicts of interest due to IQAir’s involvement in selling high-performance air purifiers, HVAC-based air cleaning, air quality monitoring units, and face masks with potential markets in Asia and North America.

Proactive Step

Efforts to combat PM2.5 pollution encompass various strategies, including enhancing emissions standards for vehicles and industries, enforcing stringent regulations, fostering cleaner energy production (such as solar, wind and green hydrogen energy), implementing energy efficiency initiatives, and promoting public awareness and behavioural changes. The integration of green and blue infrastructure, along with the establishment of active air quality monitoring and management systems, can further aid in this endeavour.

The government has taken a proactive step by launching the National Clean Air Programme (NCAP), targeting a 20-30% reduction in PM2.5 and other pollutants by 2024. This programme focuses on 102 cities, employing tailored action plans, technological interventions, and capacity-building measures. Initiatives like the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana, which provides clean cooking fuel to households, and the promotion of renewable energy sources, as well as the nationwide implementation of Bharat Stage VI emission norms (equivalent to Euro VI), aim to mitigate PM2.5 pollution from household and industrial sources. Additionally, the country collaborates with international organiaations and engages in global initiatives such as the International Solar Alliance (ISA) to combat climate change and reduce air pollution.

The significantly high PM2.5 concentration, as reported, is not just statistics but a stark testament to our shared impact on both the environment and human well-being. Such pollutants know no borders, show no regard for boundaries and impact us universally, regardless of race, nationality or belief. In our pursuit of progress and prosperity, let us commit to investing in sustainable technologies, promoting eco-friendly practices and advocating policies that prioritise public health and environmental stewardship. Ultimately, our legacy will not be gauged solely by material wealth or technological advancements, but by the purity of the air we pass on to future generations.

(The author is Professor with School of Environmental Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. Views are personal)