As per Shramavahini, a collective of rescued bonded labourers in Odisha, employers of brick kilns, stone quarries, rice mills, goat rearing, and poultry farms and many other small scale industries depend on the labour agents who in turn approach middlemen in Odisha, Bihar, Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh to find labourers at cheaper prices.

Published Date – 16 February 2024, 10:20 PM

Mancherial: Brisk activity is on at brick manufacturing units located in several parts of Mancherial, the neighbouring Karimnagar and other parts of the State come alive. The units have labourers from Odisha, Bihar, Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand, engaged in making bricks from September to May. However, the working conditions in these units are now under the scanner.

As per Shramavahini, a collective of rescued bonded labourers in Odisha, employers of brick kilns, stone quarries, rice mills, goat rearing, and poultry farms and many other small scale industries depend on the labour agents who in turn approach middlemen in Odisha, Bihar, Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh to find labourers at cheaper prices. The agents and middlemen indulge in trafficking of labourers from the four States.

“Employers of brick kilns and many other organised sectors in Telangana rely on ‘labour agents’ to find labourers from States like Odisha, Bihar, Jharkhand and Chattisgarh. The agents with the help of middlemen target labourers in distress and from poor families by luring them with cash advances ranging from Rs.30,000 to Rs.40,000 per person,” Satyaban Gahir, president of Shramavahini, told ‘Telangana Today.’

Gahir further said that many a time, labourers receive the advance cash to settle previous debts or meet an immediate need of their family, while some take it to release their mortgaged land. The managements of the kilns and quarries do not maintain record payments of labourers to cover up their exploitation and to evade legal intervention.

However, at the work sites, the labourers are under constant supervision and are allegedly denied basic rights such as freedom of movement, besides being subjected to physical violence and psychological trauma. They are left with no option but to continue to be exploited till repayment of the advance, which rarely happens.

“Unlike the ancient practice, there are no shackles or walls or any visible indicators of captivity. Instead, an invisible chain of debt and coercion runs this never-ending cycle of exploitation. Moreover, the network of middlemen, traffickers, and employers has turned it into a lucrative organized crime with huge profits and little threat from law enforcement,” says Gahir.

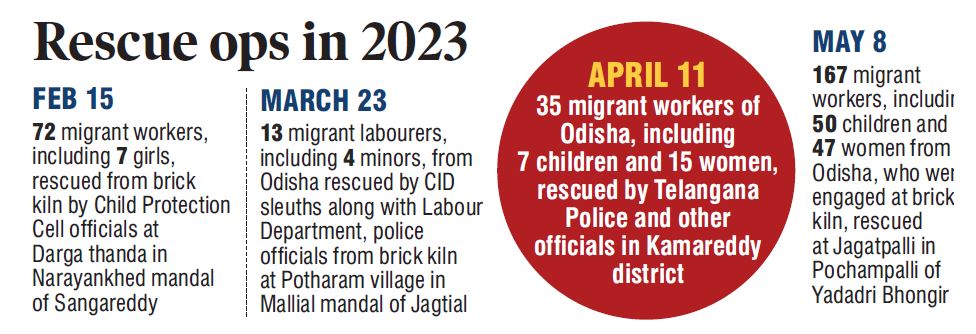

Last year, from January to December, 325 laborers, allegedly trafficked from Odisha and other States, were rescued in eight operations conducted in different parts of the State, as per information available with officials.