Mojtaba Khamenei, son of Iran’s late Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, has re-emerged in succession discussions following the reported Israeli airstrike. Long viewed as an influential behind-the-scenes figure, he is seen by some as a potential contender for Iran’s top leadership post

Published Date – 4 March 2026, 10:12 PM

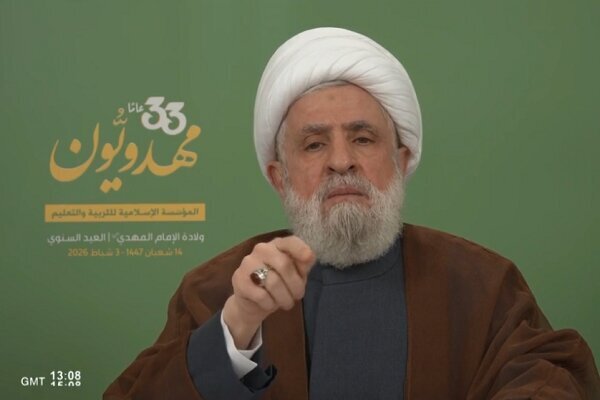

Dubai: Mojtaba Khamenei, son of Iran’s late Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, has long been considered a contender to the post of the country’s next paramount ruler – even before an Israeli strike killed his father at the start of the war last week and despite the fact he has never been elected or appointed to a government position.

A secretive figure within the Islamic Republic, Mojtaba Khamenei has not been seen publicly since Saturday, when the Israeli airstrike targeting the supreme leader’s offices killed his 86-year-old father. Also killed were the younger Khamenei’s wife, Zahra Haddad Adel, who came from a family long associated with the country’s theocracy.

Khamenei is believed to still be alive and has likely gone into hiding as American and Israeli airstrikes continue to pound Iran, though state-run Iranian media have not reported on his whereabouts.

Mojtaba Khamenei’s name continues to circulate as a possible candidate to replace his father, something that had been criticised in the past as potentially creating a theocratic version of Iran‘s former hereditary monarchy.

But now with his father and wife considered by hard-liners as martyrs in the war against America and Israel, Khamenei’s stock likely has risen with the ageing clerics of the 88-seat Assembly of Experts who will select the country’s next supreme leader.

Whoever becomes the leader will gain control of an Iranian military now at war and a stockpile of highly enriched uranium that could be used to build a nuclear weapon – should he choose to decree it.

Khamenei had occupied a similar role to that of Ahmad Khomeini, son of Iran’s first Supreme Leader, Ruhollah Khomeini – “a combination of aide-de-camp, confidant, gatekeeper and power broker,” according to United Against Nuclear Iran, a US-based pressure group.

Born into dissent

Born in 1969 in the city of Mashhad, some 10 years before the 1979 Islamic Revolution that would sweep Iran, Khamenei grew up as his father agitated against Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.

An official biography on Ali Khamenei’s life recounts one moment when the shah’s secret police, the SAVAK, broke into their home and beat the cleric. Woken up after, Mojtaba and the rest of Khamenei’s children were told their father was going on vacation.

“But I told them, there is no need to lie.’ I told them the truth,” the elder Khamenei was quoted as saying.

After the fall of the Shah, Khamenei’s family moved to Tehran, Iran’s capital. Khamenei would go on to fight in the Iran-Iraq war with the Habib ibn Mazahir Battalion, a division of Iran’s paramilitary Revolutionary Guard that would see several of its members ascend to powerful intelligence positions within the force – likely with the backing of the Khamenei family.

His father became the supreme leader in 1989, and soon Mojtaba Khamenei and his family had access to the billions of dollars and business assets spread across Iran’s many bonyads, or foundations funded from state industries and other wealth once held by the shah.

His own power rose alongside his father’s, working within his offices in downtown Tehran. US diplomatic cables published by WikiLeaks in the late 2000s began referring to the younger Khamenei as “the power behind the robes.” One recounted an allegation that Khamenei actually tapped his own father’s phone, served as his “principal gatekeeper” and had been forming his own power base within the country.

Khamenei “is widely viewed within the regime as a capable and forceful leader and manager who may someday succeed to at least a share of national leadership; his father may also see him in that light,” a 2008 cable read, also noting his lack of theological qualifications and age.

“Mojtaba is, however, due to his skills, wealth, and unmatched alliances, reportedly seen by a number of regime insiders as a plausible candidate for shared leadership of Iran upon his father’s demise, whether that demise is soon or years in the future,” it said.

Khamenei has worked closely with Iran’s paramilitary Revolutionary Guard, both with commanders of its expeditionary Quds Force and its all-volunteer Basij that violently suppressed nationwide protests in January, the US Treasury has said.

The United States sanctioned him in 2019 during the first term of U.S President Donald Trump over working to “advance his father’s destabilising regional ambitions and oppressive domestic objectives.” That includes allegations that Khamenei, from behind the scenes, supported the election of hard-line President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad in 2005 and his disputed re-election in 2009 that sparked the Green Movement protests.

Mahdi Karroubi, who was a presidential candidate in 2005 and 2009, denounced Khamenei as “a master’s son” and alleged he interfered in both votes. His father reportedly said at the time that Khamenei was “a master himself, not a master’s son.”

Powers of the supreme leader at stake

There has been only one other transfer of power in the office of the supreme leader of Iran, the paramount decision-maker since the country’s 1979 Islamic Revolution. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini died at age 86 after being the figurehead of the revolution and leading Iran through its eight-year war with Iraq.

Now the new leader will come on board after the 12-day war with Israel, and as a US-Israeli war with Iran is seeking to eliminate Iran’s nuclear threat and military power, hoping also that the Iranian people will rise up against the Iranian theocracy.

The supreme leader is at the heart of Iran’s complex power-sharing Shiite theocracy and has final say over all matters of state. He also serves as the commander-in-chief of the country’s military and the Guard, a paramilitary force that the United States designated a terrorist organisation in 2019, and which his father empowered during his rule.

The Guard, which has led the self-described “Axis of Resistance,” a series of militant groups and allies across the Middle East meant to counter the US and Israel, also has extensive wealth and holdings in Iran. It also controls the country’s ballistic missile arsenal.