By Pramod K Nayar

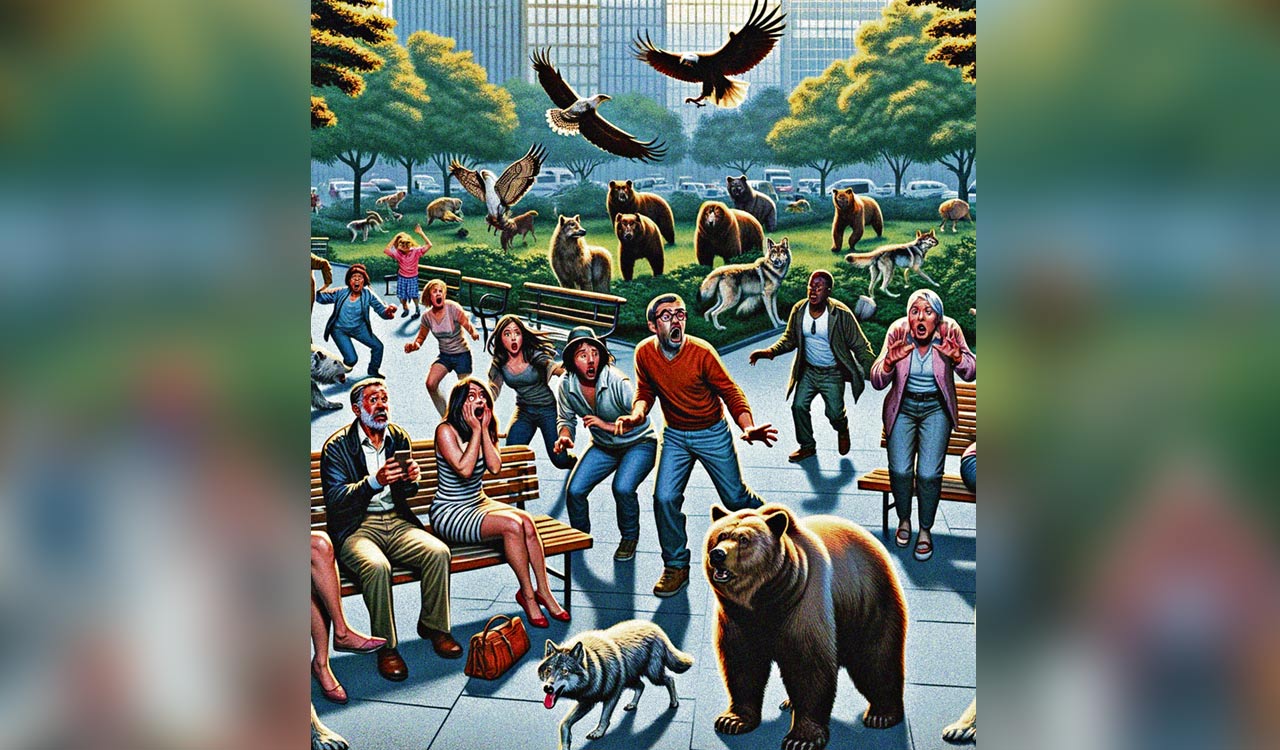

Humans trapped on lakes infested with crocodiles, on a rocky outcrop surrounded by sharks, inside an underwater cave besieged by squids or some unknown life forms…the list of popular representations of such under-attack humans grows exponentially daily, even if we discount alien species and invasive life forms arriving on earth. A staple of the horror genre, ecohorror presents not the all-conquering human, but one at the mercy of the nonhuman. This ecohorror cinema shares borders with survivor-horror as well.

Alfred Hitchcock arguably inaugurated ecohorror with The Birds (1963) where the birds attack humans for no apparent reason. But the film that really made the genre a commercial success was Steven Spielberg’s Jaws (1975). Based on Peter Benchley’s novel of the same name (besides Jaws, he authored The Deep, also made into a successful film), Jaws depicted the human-nonhuman encounter as a fight for survival. While mostly dealing with animal-predation of humans, some such as The Happening have plants at the root of the horror—what the critic Dawn Keetley terms ‘vegetal horror’ (which is not the fear of vegetables).

We now have numerous recent examples of ecohorror cinema (what is sometimes called ‘creature features’): The Meg, Lake Placid, Crawl, The Shallows, among others. Rats, snakes, bears, piranha, sharks, crocodiles and alligators, spiders, birds — humanity, it would appear, is afraid of any species that swims, walks, slithers or flies. (There is a subgenre, represented by films like The Fly or biomutation-horror films in sci-fi where humans become other species, or the predator, like a Godzilla, is the outcome of some human practice, and as a consequence generates horror.)

Outside Human Control

The fundamental premise of ecohorror is that the natural world, when humans interface with it intentionally or unintentionally, is beyond human control. In cases like The Shallows or Lake Placid, humanity’s interface with the ocean or lake mutates into a confrontation with the habitual residents of the terrain. In most cases, humanity leaves its cultural and geographical boundaries and enters the natural world, for recreation, escape or exploration.

That is, ecohorror hinges on the human’s, usually non-domestic, confrontation with the nonhuman. Ecohorror reenacts a very old trope in literature and culture: of nature versus culture. Humanity, representing culture, crosses borders when it enters the world of the bear, the shark or the crocodile (although one subgenre also focuses on the animals entering human dwelling spaces).

The sense of being besieged is accompanied by the sense (moral, even ethical) that humanity was not supposed to invade the habitats of the nonhuman. Humanity, implies ecohorror, is a disruptive presence in the lake, ocean or forest. This means, there is a larger message one could take away from the often kitschy eco- and survivor horror: that humanity has endangered the world of the nonhuman, entered it, violated it and therefore needs to pay the price.

Planetary Fears

Ecohorror, in a sense, is the opposite of cosmic horror — films about alien invasion — being very much earth-bound. Ecohorror embodies planetary fears where humanity is vulnerable. It is a veiled expression of an ecological anxiety: humanity is not the master of the universe, is not an all-conquering creature in a world of other critters.

As a result of ecohorror, humanity has started viewing the earth not as simply a set of resources, a promising and potentially viable terrain. We share space with other critters, we depend on these other critters — including plants, crabs and bacteria, as some recent fiction such as Richard Powers’ The Overstory, Amitav Ghosh’s The Hungry Tide and Alexis Smith’s Marrow Island envisions. As Ghosh would say of the crabs:

The crabs emerge at dawn and at dusk to salvage the rich haul of leaves and other debris left behind by the retreating tide. [They form] a fantastically large proportion of the system’s biomass and constitute the keystone species of the entire ecosystem [and keep] the mangroves alive by removing their leaves and litter.

Ecohorror suggests that we have reinvented the planet, terraformed it (terraforming: the transformation of another planet for human life), but this terraforming has perhaps upset the balance. In other words, ecohorror tells us that humanity has done unspeakable things to the planet and now the planet’s other denizens are attempting a reclamation, or simply saying to intrusive humans: stay out.

Planetary Fears to Ecophobia

For critics like Simon Estok humanity now exhibits an ecophobia, an irrational fear of the natural world. Estok and later critics argue that ecophobia stems from a fear of the loss of control and a certain uncertainty about the natural world. For Estok, ‘representations of nature as an opponent that hurts, hinders, threatens, or kills us’ are instances of the ecophobic.

Ecophobia is on par with homophobia or race-phobia, according to Estok, and embodies a certain angst-ridden, fearful attitude towards the nonhuman world. It is also rooted, as we can see in the films, the belated recognition that human cultural norms have cost the earth, literally.

When, for instance, Spielberg attempts an ecohorror in his Jurassic Park, he presents the ‘natural’ world of the dinosaurs as entirely man-made, fitting into human cultural norms of what the prehistoric creatures should be: safe, entertaining, money-making. The source of the horror here is that the creatures never received the memo, or didn’t understand it (MS Word doesn’t do dino-speak) — that this is what they are supposed to be.

Cultural norms have shifted — this is of course the critic Noël Carroll’s famous description of horror in general — because humanity is not only not in control, it is under the active threat of attack from the natural world whose naturalness has been eroded considerably by humanity. Nature-attack, as the ecohorror genre sees it, is not so much about disaster as it is about a melodramatic rethink of the human-nonhuman relationship.

Skrich-skrich, the critters are coming.