The iconic promise that ‘even a person in Hawai chappal can fly’, transformed Indian Aviation. IndiGo’s meltdown now lays bare the fragility of that dream

Updated On – 13 December 2025, 10:23 PM

By Praveen Bose

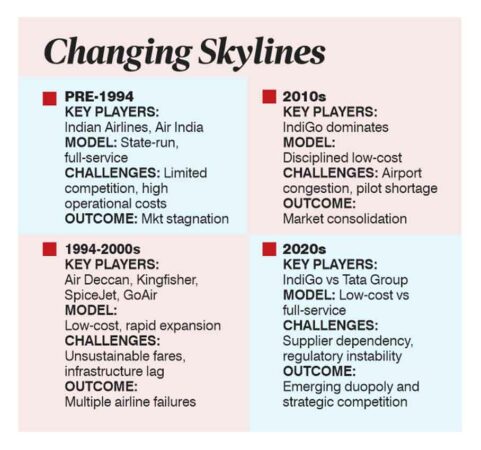

The story of Indian aviation is a gripping saga of ambition, innovation, and the harsh realities of economics and infrastructure. It is a tale not just of individual airlines’ successes or failures, but also of an entire industry’s struggle to balance rapid growth with sustainable profitability. The journey from a state-controlled duopoly to a vibrant, competitive market has been marked by turbulence, both literal and metaphorical, as airlines grappled with global economic shifts, regulatory changes, and the daunting task of building an aviation ecosystem from scratch.

Indian aviation has journeyed from the euphoric days of deregulation and the rise of low-cost carriers to the current era of consolidation and strategic competition. The dream of making flying accessible to the masses, epitomised by the iconic phrase “even a person in Hawai chappal can fly”, transformed the industry but also exposed its fragility. Systemic challenges have plagued the sector, including infrastructure bottlenecks, human resource deficits, and supplier dependencies, which continue to shape its future.

When the Skies Opened

The watershed moment in Indian aviation came in 1994 with the Air Corporations Act, which dismantled the state-run duopoly of Indian Airlines and Air India. This legislative change opened the skies to private players, igniting a gold rush in the late 1990s and early 2000s. A colourful array of airlines emerged, including ModiLuft, East-West, Damania, Sahara, Air Deccan, Kingfisher, SpiceJet, GoAir, and Paramount, with each vying to carve a niche in the newly liberalised market.

At the heart of this revolution was Captain GR Gopinath’s Air Deccan, which pioneered the Low-Cost Carrier (LCC) model in India. Gopinath’s vision was sociological as much as commercial: to democratise air travel, making it accessible to the common man. The idea that “even a person in Hawai chappal can fly” became a powerful metaphor for the new India, where air travel was no longer the preserve of the elite. Fares on routes like Bangalore to Hubli dropped below train ticket prices, unleashing a wave of first-time flyers, middle-class families, students, and small businessmen, who flooded airport terminals.

This era was characterised by irrational exuberance. Airlines expanded rapidly, fueled by rising incomes, cheap global oil prices, and relentless optimism. The model was simple: fill seats at any cost. Fares were often priced below operational costs, and the race for market share trumped profitability. The sector boomed, but the foundations were fragile. The aviation ecosystem, including airports, air traffic control, pilot training, and maintenance, struggled to keep pace with the explosive growth. Skilled personnel, from pilots to air traffic controllers, were in critically short supply. Infrastructure, especially at congested metros like Mumbai, groaned under the pressure.

The Great Shakeout

The initial boom was followed by a brutal reckoning. One by one, the flaws in the model proved fatal.

Kingfisher Airlines, the poster child of glamour and ambition, collapsed spectacularly under a mountain of debt, its founder Vijay Mallya’s dreams extinguished. Air Deccan was sold to Kingfisher and eventually faded away. Air India, the national carrier, bled billions, surviving only through government bailouts. SpiceJet, GoAir, and others lurched from crisis to crisis, saved repeatedly by promoters or external investors.

The industry entered a cycle of losses, debt, and desperate mergers. The dream of making flying accessible had come at a cost — one that many airlines couldn’t survive. The sector’s fragility was exposed by its inability to sustain profitability amid cutthroat competition and rising costs.

Low-Cost Revolution

Amid the carnage, one airline seemed to have cracked the code: IndiGo. Founded in 2006, IndiGo eschewed the flamboyance of its peers and focused on disciplined costs and operational rigour. Its model wasn’t just about low fares; it was about low, disciplined costs and operational efficiency.

IndiGo’s genius lay in the details:

- Single aircraft type (Airbus A320) for training, maintenance, and crew efficiency.

- Sale-and-leaseback financing, which freed up capital and provided a steady stream of profits from aircraft trading.

- Fanaticism about on-time performance and aircraft utilisation, turning planes around in 25 minutes.

- No-frills, standardised service that eliminated complexity and kept costs down.

While competitors chased market share with aggressive discounting, IndiGo chased cost leadership with zeal. It wasn’t selling a luxury experience or even a particularly warm one; it was selling a reliable, affordable utility. As others foundered, IndiGo’s consistency won passenger trust and market dominance, climbing to an unprecedented 60% domestic share. Yet even IndiGo’s success couldn’t mask the sector’s persistent, systemic gaps:

- Airport congestion at major hubs like Delhi and Mumbai imposed hard ceilings on efficiency.

- Chronic pilot shortages led to bloated and volatile HR costs, sometimes consuming 25-35% of a flight’s revenue.

- Supplier dependency on global manufacturers (Airbus and Boeing) and engine makers created single points of failure.

- Regulatory instability and frequent policy changes made long-term planning difficult.

The New Reality: A Hardening Duopoly

The Indian aviation landscape is now shifting fundamentally. The rise of the Tata Group airlines, following the merger of Air India, Vistara, AIX Connect, and Air India Express, creates a strong, well-funded full-service competitor for the first time since the Kingfisher era.

This is no longer a sector of one giant and many struggling minnows; it is hardening into a duopoly with a few niche players. This new competition will test IndiGo’s model like never before. The Tata group is investing in both service quality and fleet modernisation, forcing IndiGo to move beyond its pure-play LCC roots.

IndiGo is now venturing into longer international routes (with its A321XLR order) and potentially more complex service offerings. It is being pushed to evolve, but evolution brings complexity, and complexity is the enemy of the low-cost model.

Can Indian Aviation Stabilise?

The ongoing operational woes at IndiGo—grounded planes, flight cancellations, slipping on-time performance—are not isolated events. They are the convergence of India’s aviation gaps onto its largest player.

The Hawai chappal revolution achieved its goal: India is now the world’s third-largest domestic aviation market. But the sector has been running on the heroics of individual companies, not on the strength of a robust, integrated system. The cracks in infrastructure, the unsustainable squeeze between high fixed costs and low fare expectations, supplier dependency, and economic sustainability were always there, visible in the corpses of fallen airlines.

IndiGo, with its brilliant execution, flew higher and longer than anyone else, seemingly immune to gravity. But gravity, in the form of these systemic challenges, always exerts its force. The current crisis is a stark reminder that no airline, no matter how dominant, is an island. Its fate is inextricably linked to the ecosystem it operates in.

The next chapter of Indian aviation will be defined by how well the duopoly manages these inherited burdens and whether the ecosystem can finally mature to support the dreams it once so readily sold.

The story of Indian aviation is a profound reflection of a nation’s economic ambitions colliding with the hard realities of infrastructure, economics, and execution. The sector’s journey from a state-controlled duopoly to a chaotic, competitive market and now to a consolidating duopoly illustrates the challenges of rapid growth without a robust ecosystem.

The dream of making flying accessible to the masses was realised, but at a cost. The industry’s future hinges on addressing systemic gaps, infrastructure, human resources, supplier risks, and regulatory stability to achieve sustainable profitability and growth.

As India’s aviation sector enters its next phase, the question remains: Can it finally stabilise and soar, or will turbulence continue to define its path?

***********

Flying into history

- Modiluft was a short-lived but notable airline that operated in the mid-1990s. Launched with support from Lufthansa, it set strong safety standards, reliable on-time performance, and a rare three-class cabin layout on domestic routes. It remains an interesting chapter in India’s early era of aviation deregulation, though it ceased operations in 1996

- East West Airlines was India’s first national-level private airline, launched in the early 1990s after aviation deregulation opened up the sector to private players. It expanded quickly but shut down in 1996 after operational and financial difficulties, marking a dramatic rise and fall chapter in India’s aviation history.

- Damania Airways was a Mumbai-based private airline that operated from 1993 to 1997, founded by brothers Parvez and Vispi Damania. Known for its focus on premium in-flight service and leased Boeing 737 200 aircraft, it eventually shut down after financial struggles and its acquisition by the NEPC group

- Sahara Airlines, founded in 1991 as Sahara India Airlines, was later rebranded as Air Sahara and became one of India’s prominent private carriers. It was acquired by Jet Airways in 2007 and operated as JetLite until ceasing operations in 2019

- Air Deccan, India’s pioneering budget airline, experienced two major phases: its original success, making air travel affordable, and its sale to Kingfisher in 2007-08 (becoming Kingfisher Red). Gopinath, however, secured the Air Deccan trademark shortly after, preventing Mallya from using it. Gopinath later relaunched Air Deccan in 2017 with a focus on regional flights, leveraging the brand name he had kept. But the second innings ended with Covid-19 taking its toll in 2020

- Kingfisher Airlines, launched in 2005 by Vijay Mallya’s United Breweries Group, quickly became known for its premium service and stylish branding. Despite once holding the second-largest share of India’s domestic market, the airline ceased operations in 2012 due to mounting financial losses and debt.

- SpiceJet began operations in 2005 and survived through bailouts. It now serves over 70 destinations. Despite financial challenges in recent years, it continues to expand its fleet and routes, recently adding Boeing 737 aircraft and increasing daily flights to meet growing demand.

- GoAir, founded in 2005 by the Wadia Group, was an Indian low-cost airline headquartered in Mumbai. It rebranded as Go First in 2021 but ceased operations in May 2023 due to financial difficulties

- Paramount Airways, founded in 2005, was headquartered in Chennai. It was known for pioneering the use of Embraer E-Jets in India. It primarily served business travellers across South and East India, but ceased operations in 2010 following legal disputes with aircraft lessors

(The author is a former journalist who also tracked the aviation sector)