Signing the accord offers the symbolic advantage of a “seat at the high table,” but strategic caution must guide New Delhi’s choices

Published Date – 20 February 2026, 09:35 PM

By Brig Advitya Madan (retd)

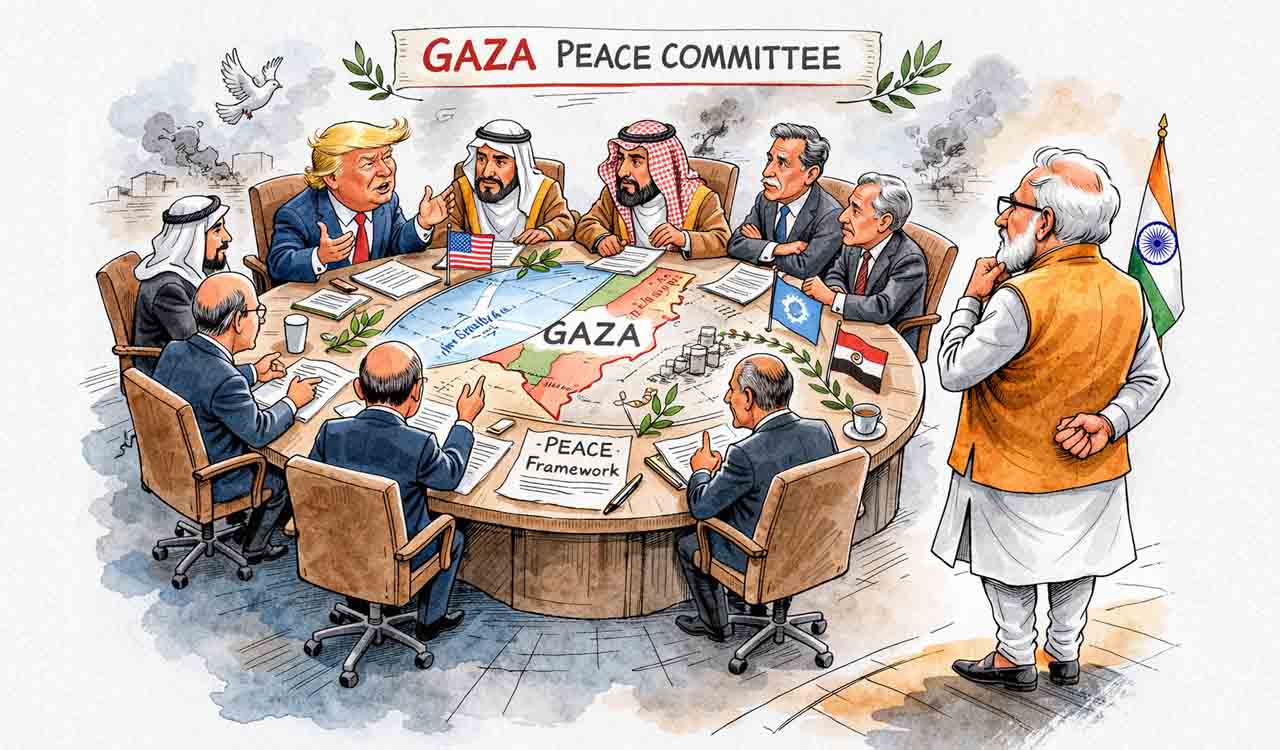

Of the two developments linked to Gaza, the first was the inaugural meeting of the proposed ‘Board of Peace for Gaza,’ held on February 19. The second is Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s scheduled visit to Israel on February 25. These events, taken together, make this an appropriate moment to reflect on whether India should associate itself with the newly proposed Gaza peace architecture.

A brief backdrop is essential. The Gaza Strip is a narrow enclave roughly 41 kilometres long and 10 kilometres wide. On its eastern flank lies a heavily fortified perimeter separating it from Israel. On October 7, 2023, Hamas militants breached this barrier, killing approximately 1,200 Israelis and taking around 250 hostages. What followed was a prolonged and devastating conflict. After nearly 15 months of war, a ceasefire was declared on January 19, 2025. However, it lasted barely two months, collapsing on March 18, 2025. During that brief window, only three Israeli hostages and 90 Palestinian prisoners were exchanged — a modest outcome relative to the scale of the conflict.

Ceasefire Framework

It was only on October 9, 2025, that the United States brokered a broader ceasefire framework, inviting 60 world leaders to endorse a ‘Board of Peace for Gaza’. At a subsequent global economic summit, 26 countries signed the Gaza Peace Accord, pledging $5 billion in financial assistance and committing troops to an international stabilisation force. India has so far not taken a position.

The Gaza peace plan is structured in two phases. Phase One focuses on stabilisation and security; Phase Two envisages an economic and political settlement. Yet, of the 20 provisions in the plan, only three have been partially implemented: a fragile ceasefire frequently violated, limited exchanges of Israeli hostages and Palestinian prisoners, and the opening of the Rafah crossing solely for medical evacuations. The deeper issues remain unresolved.

The trust deficit between Israel and Hamas continues to impede progress. Israel insists that Hamas must surrender its weapons — a demand Hamas categorically rejects. Hamas, for its part, demands a role in governing Gaza, something Israel refuses to accept. Without movement on these core issues, the peace process risks remaining procedural rather than substantive.

India’s Options

India must therefore carefully weigh its options before joining the Board of Peace. Signing the accord may offer the symbolic advantage of a “seat at the high table” in shaping post-conflict Gaza. But symbolism cannot substitute for strategic prudence.

One of the most significant concerns is structural. The Board of Peace is chaired by Donald Trump in his personal capacity, rather than by the incumbent US President ex officio. This raises serious questions about institutional continuity. What happens when a new US administration assumes office in January 2029? Would the Board’s decisions bind a future American government? Would India be aligning itself with an initiative whose longevity depends on the political fortunes of an individual?

India can aid humanitarian relief and reconstruction without formally joining a Board whose structure, mandate, and longevity are uncertain

India has consistently demonstrated strategic autonomy in recent years — whether in navigating the Russia-Ukraine conflict, balancing relations during tensions between Israel and Iran, or managing trade frictions with the United States. Associating with a body that could potentially take politically charged decisions may constrain India’s diplomatic flexibility. There is also the broader concern that such extra-UN mechanisms could, over time, dilute or supplant the authority of established multilateral institutions, such as the United Nations. The implications of that shift could extend beyond Gaza to other international disputes, including those directly affecting India.

Another dimension relates to the nature of the initiative itself. President Trump has frequently framed the Palestinian question through an economic lens — prioritising reconstruction funding, investment packages, and development corridors. While economic revival is vital, the conflict is fundamentally political, rooted in competing national aspirations and questions of sovereignty. If India becomes a member of this Board, it may find itself navigating delicate diplomatic terrain.

India’s ties with Israel are deep and multifaceted, encompassing defence cooperation, counter-terrorism, cybersecurity, and high-technology transfers. India imports significant defence equipment from Israel, including night-vision devices and unmanned aerial vehicles. Simultaneously, India’s energy security depends heavily on Arab partners, and it has historically supported a two-state solution recognising Palestinian aspirations. Joining the Board could complicate this careful balancing act.

Operational concerns also merit attention. Unlike UN peacekeeping missions operating under Chapter VII mandates of the UN Charter, this Board appears to lack a clearly defined enforcement framework. Without a robust legal mandate and defined rules of engagement, any international stabilisation force risks ambiguity. Indian troops, if deployed, could find themselves caught between the Israel Defense Forces and Hamas militants without clarity on escalation thresholds. Such a scenario would expose India to military and reputational risks.

The Global South

India’s standing in the Global South is another consideration. Over the past decade, India has cultivated an image of principled independence, neither aligning reflexively with the West nor opposing it reflexively. Many developing countries view India as a credible voice precisely because of this balanced approach. Participation in an initiative perceived as US-driven could erode that credibility. Unlike smaller states that often align out of necessity, India has the strategic weight to maintain autonomy — and that autonomy has been a source of diplomatic capital.

There is also the question of accountability. If the peace process falters — particularly if the envisioned two-state solution proves unattainable — signatories may share responsibility. A recent statement by a Hamas leader rejecting disarmament and foreign oversight underscores the fragility of the current arrangement. India must ask whether it is prepared to shoulder the political costs of failure.

Finally, questions remain regarding the utilisation and transparency of pledged funds. Clarity on disbursement mechanisms, oversight, and measurable outcomes is essential before any financial commitments are made.

Taken together, these considerations suggest that India should proceed with caution. Engagement need not mean endorsement. India can support humanitarian relief, reconstruction assistance, and diplomatic dialogue without formally joining a Board whose institutional design, mandate, and long-term viability remain uncertain.

New Delhi would do well to observe developments closely before making a commitment. In a volatile region where alignments shift rapidly, and outcomes remain unpredictable, restraint is not passivity — it is prudence.

For now, strategic autonomy remains India’s strongest asset.

(The author is a retired Army officer)