As Telangana’s per capita income rises and demographic indicators improve, its share in central tax devolution shrinks, exposing the contradictions within the spirit of cooperative federalism

Published Date – 4 February 2026, 11:20 PM

By Vidyasagar Reddy Kethiri

The dust has settled on the Union Budget 2026–27, but in Hyderabad, the air remains thick with a sense of déjà vu. As the 16th Finance Commission (FC) recommendations come into effect from April 2026, the numbers tell a story not of “cooperative federalism” but of a deepening fiscal divide. For Telangana, the narrative has shifted from the excitement of a newly formed State to the frustration of an economic powerhouse being quietly penalised for its own efficiency.

The Arithmetic of Injustice

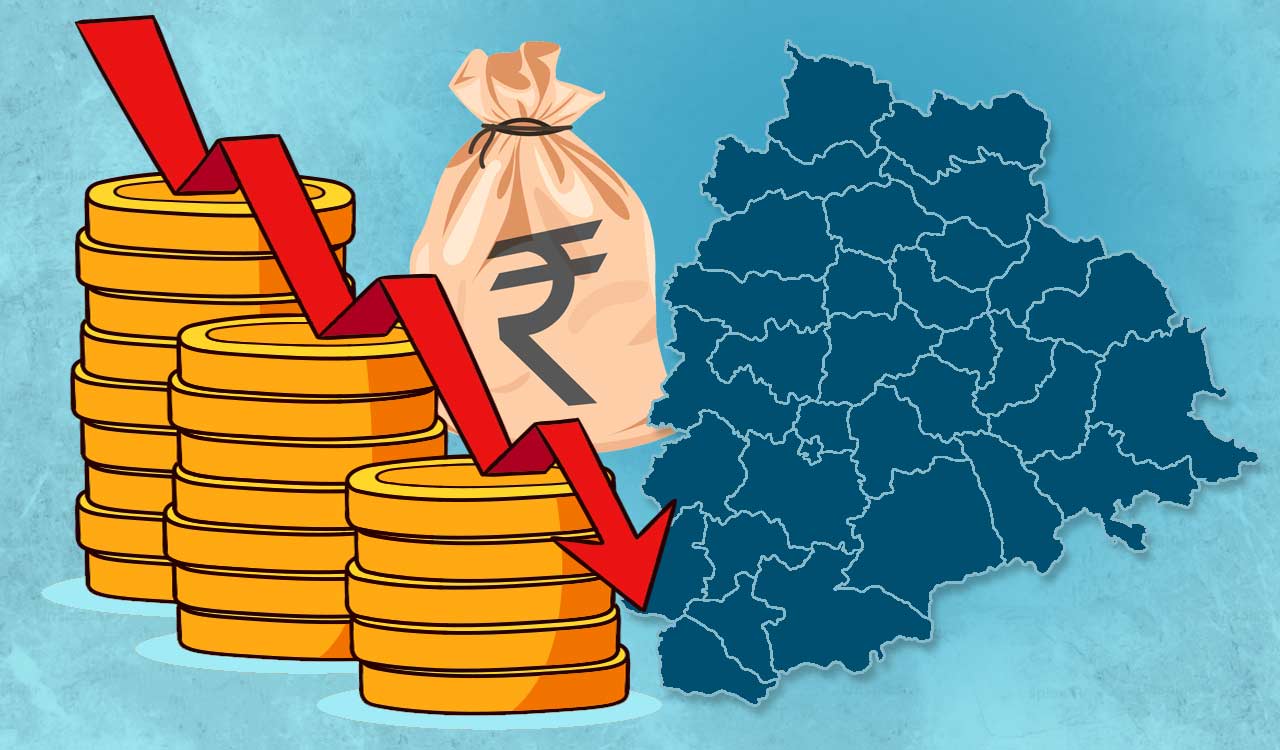

The most visible disparity lies in the tax devolution formula recommended by successive Finance Commissions. Under the 14th Finance Commission (2015–20), Telangana’s share in the divisible pool of central taxes stood at 2.43%. This was reduced to 2.10% under the 15th Finance Commission (2021–26).

The much-anticipated 16th Finance Commission interim report, tabled on February 1, 2026, offers only a marginal increase of about 0.07%, raising Telangana’s share to approximately 2.17%.

In contrast, Gujarat — a State with a broadly similar industrial profile — enjoys a significantly higher share of about 3.48%.

While Gujarat is undoubtedly a growth engine, the divergence in treatment suggests that Telangana is being subjected to what economists increasingly describe as a “success penalty”.

How Tax Devolution is Decided

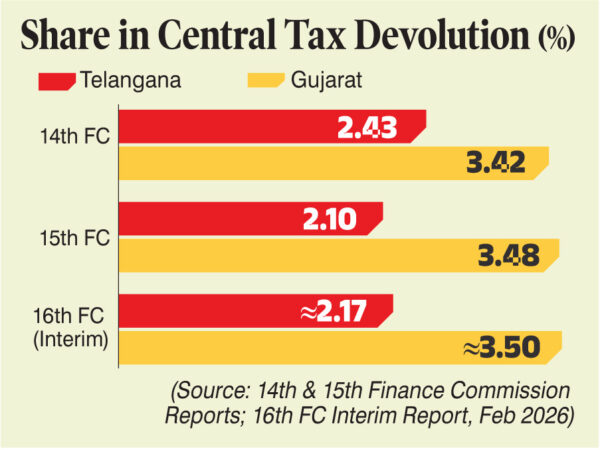

Under Article 280 of the Constitution, the Finance Commission recommends how the divisible pool of central taxes should be distributed among the States. The 15th Finance Commission adopted the following criteria for horizontal devolution:

The overwhelming dominance of Income Distance (45%) lies at the heart of Telangana’s disadvantage.

The “Income Distance” Formula

Income Distance measures the gap between a State’s per capita income and that of the poorest State. The larger the gap, the more a State is deemed to “need” central support. While this principle aims at equity, its unintended consequence is to punish States that successfully raise incomes and stabilise population growth.

States such as Telangana, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and Maharashtra that invested early in industry, IT, pharmaceuticals and infrastructure are classified as fiscally “less deserving”, even though they contribute disproportionately to central tax revenues.

Thus, when Telangana improves its per capita income and demographic indicators, its reward is a reduced share in central taxes. This creates a perverse incentive structure: performance is penalised, while stagnation is rewarded. Such an approach contradicts the spirit of cooperative federalism, which was meant to balance equity with efficiency.

A Tale of Two Hubs: GIFT City Vs Scrapped ITIR

The bias is not confined to routine transfers. It is more evident in the allocation of central-sector mega projects that determine a State’s long-term economic future. Hyderabad was promised the Information Technology Investment Region (ITIR) in 2013 — a project projected to attract Rs 2.19 lakh crore in investment and generate nearly 15 lakh jobs. The Centre later scrapped ITIR citing “policy changes”.

At the same time, massive public resources were channelled into Gujarat’s GIFT City and into semiconductor clusters at Dholera and Sanand through generous subsidies and Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) schemes.

After the Centre rejected NITI Aayog’s recommendation of Rs 24,000 crore, Telangana borrowed funds to support essential water and irrigation projects like Kaleshwaram — projects that were not populist schemes but critical infrastructure investments

Even the Union Budget 2026–27 reinforces this asymmetry. The newly announced “Biopharma Shakti” scheme with an outlay of Rs 10,000 crore makes no reference to Telangana, despite Hyderabad’s Genome Valley producing nearly one-third of the world’s vaccines and hosting India’s largest life-sciences ecosystem.

According to DPIIT (Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade) investment intention data (2025–26), Telangana accounts for nearly 10% of India’s total proposed investments. Ignoring such a State in flagship industrial schemes is not merely a political oversight; it is economic self-harm.

The Off-Budget Stranglehold

Perhaps the most damaging injustice lies in the Centre’s treatment of State borrowing. After the Centre ignored NITI Aayog’s recommendation to grant Telangana Rs 24,000 crore for Mission Bhagiratha, the State had no choice but to borrow heavily to fund drinking water and irrigation projects such as Kaleshwaram. These were not populist schemes but core infrastructure investments.

Subsequently, the Centre retroactively included borrowings of state-run corporations within Telangana’s Net Borrowing Ceiling (NBC). This “off-budget correction” sharply reduced the State’s fiscal space and crippled its ability to finance infrastructure such as the Regional Ring Road (RRR) and Hyderabad Metro Phase II — both of which found no mention in the February 2026 Budget speech.

Forced to self-finance projects that other States receive as central grants, Telangana’s debt is projected to exceed Rs5 lakh crore by 2026. This is not a story of fiscal indiscipline; it is the direct outcome of systematic denial of central support.

Growth without Reward

Telangana’s real Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP) growth rate for FY 2024–25 is estimated at about 5.8% (Source: Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation provisional estimates and Telangana Economic Survey 2025–26). Its per capita income has risen faster than the national average over the past decade.

These achievements are national assets, not regional inconveniences. Penalising high-performing States weakens national productivity and breeds long-term resentment.

A Call for Real Federalism

The cumulative impact of reduced tax devolution, cancellation of job-generating projects, denial of strategic industrial schemes and tight borrowing controls reveals a troubling pattern. Fiscal federalism is no longer neutral; it is selective.

If the 16th Finance Commission does not move towards a formula that gives greater weight to GSDP contribution and fiscal effort — and reduces excessive reliance on population and income distance — the “Telangana model” of self-funded development will soon hit a centrally imposed ceiling.

As India marches toward Viksit Bharat 2047, cooperative federalism must mean more than rhetoric. It must mean fairness, transparency and reward for performance.

(The author is Consultant, Training Coordination Division, Arun Jaitley National Institute of Financial Management, Faridabad, Haryana)